That Article Devaluing Music Education Was Bad

But Music Education's Response to it Wasn't Any Better

Last week was the latest meltdown in the world of music education. This time, the outrage was levied towards the educational magazine Junior Scholastic concerning an article in one of their most recent issues. In this article, part of their “Debate It” series, the question “Should Kids Learn Music in School?” was presented with responses ostensibly provided by two elementary-aged students. Kaleeyah Flores argued for the inclusion of music in schools by saying that her music class was helpful in lifting her mood and relieving stress. She also cited the ability of music class to teach children how to work hard and to learn teamwork (something she mentioned is also learnable from doing group projects and playing team sports).

The antagonist, Aaron Van Dam, offered a different point of view. While he expressed a belief that music is important (though without saying why), he argued for a more practical approach to class offerings. His stance was that time should be dedicated to STEM classes as, according to him, these are subjects most likely to be part of future jobs. He further stated that music programs take away from the other limited resource, money, which he argued should be used to purchase textbooks or computers. Music education, according to Aaron, should happen outside of school.

You can probably guess what happened once word of this article made its way through the various music education social media echo chambers. Like every other time before, when someone outside of music education publicly diminishes the value of music programs, the music education tribe pushed back.1 Only the pushback was big on vociferous indignation but weak in eliciting any impactful change. What the music education profession can’t or won’t acknowledge, is that most Americans outside of its own bubble would agree with Aaron. If this bothers you then you’re going to really get your feathers ruffled by the next truth: music education deserve much of the blame.

(Record scratch)...”Say WHAT?!?!?” I can hear the indignation of nearly every music educator reading this so allow me to elucidate on this point:

Before I get to that, I first want to acknowledge the music education profession for its tireless advocacy efforts over the past several decades. There is a long history of strong, defensive reactions by the music education bubble which consists of individual teachers, parents & students involved in school music programs, and from some supportive school administrators. Professional leaders from organizations such as the National Association for Music Education (NAfME) and the New York State School Music Association (NYSSMA) wrote swift letters to Suzanne McCabe, Managing Editor of Junior Scholastic, defending music education as part of a well-rounded education and expressing their disappointment in Scholastic for even debating that stance.

To Scholastic’s credit, Senior Vice President Anne Sparkman responded to the criticism, apologizing for the negative impact the article had on advocacy work and insensitivity towards music teachers.

It was a well-written, seemingly sincere response. However, as seems to always be the case in these situations, it seems an apology and a promise to do better is all that music educators can expect from the repartee.

So why is that? Why is music education still fighting for respect after so many similar instances over decades? Why does music education continue to struggle for adequate resources and enough participation needed to establish itself as an integral part of American schools? What are music educators doing to help/hinder these efforts? Let’s look and see:

WHY IS MUSIC EDUCATION STRUGGLING TO BE AN INTEGRAL PART OF AMERICAN SCHOOLS?

Music education is not meeting the needs of the American public.

The best way to motivate someone towards an action is to convince them it meets a specific need they have. One reason why music education struggles is because it has done a poor job of identifying, explaining, and meeting the needs of the public. Let’s examine a couple of these most pressing needs:

Music as an integral part of being human.

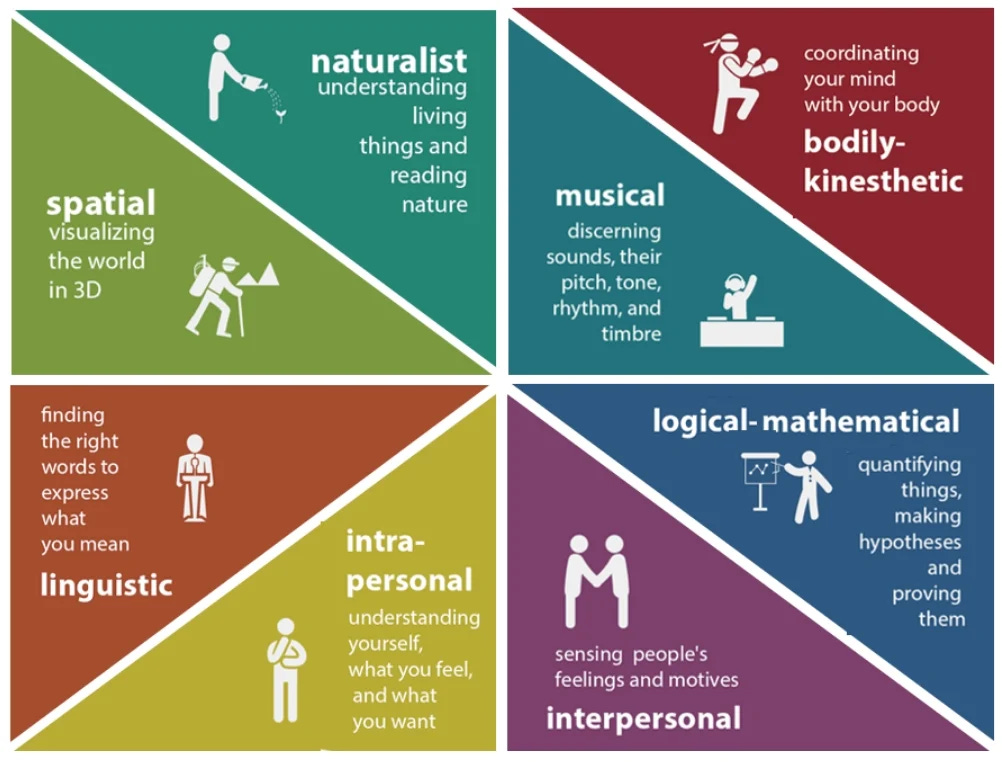

In 1999, developmental psychiatrist and research. Howard Gardner, spoke at a conference of music educators on the topic of music in education.2 At the time, his Theory of Multiple Intelligences was increasingly finding ground within music education philosophy and pedagogy. Gardner made several observations regarding music as a uniquely human characteristic and experience. His initial point was that music is one of between 7-9 different types of intelligence possessed by every person. As such, music must be exercised and disciplined along with the other intelligences.

Gardner also discussed music as a uniquely human potential which students should be provided opportunities to meet. Other arguments he made for music education include its usefulness for learning a craft; its ability, along with the other arts, to foster creativity, exploration, & affective domain development; and perhaps my favorite statement, in his own words…

“human beings have done lots of terrible things, and we guess we need to know about them. But we've also done some wonderful things. Classical music is a wonderful thing, and the symphony orchestra is a wonderful thing, as are jazz, rock, and other forms of music. You shouldn't be deprived in your life from knowing the great things humans have done.”

The work of educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom, who developed the theory of learning domains, provides a complimentary perspective. As with the 7-9 intelligences identified by Gardner, every human being possesses the ability to learn, develop, and evolve in one of three learning domains: the cognitive domain (knowledge), the psychomotor domain (skill), and the affective domain (emotions). Music education, along with all the arts, provides a unique opportunity to provide learning experiences in all three domains, a claim that no other common school discipline or subject can make.

Unfortunately, music education has been inconsistent in developing these integral humanistic aspects for all students in American schools. This isn’t completely the fault of music teachers. Much of the blame can be placed on the misguided priorities and culture of American education and society. Nevertheless, music education shares some responsibility by embracing an unbalanced culture focused much more on the development of psychomotor over cognitive or affective domains.3

It is next to impossible to find a single human being who doesn’t like music in some form or fashion. Given this, its stands to reason that virtually every student in America would participate in school music activities if educational institutions and music educators were adequately responsive to this.

Needs driven by scarcity mindset

An even more basic unmet need is to assuage the budgetary challenges that concern school administrators, government officials, and the public. It’s no secret that music and other humanities are underfunded, under prioritized, and usually the first to be cut during periods of austerity. The lack of prioritization and support of education writ large is a disastrous reflection of a strong presence of anti-intellectualism and selfishness that is currently a hallmark of American culture. Of course, music education is negatively impacted by the collective mindset that devalues education in general. So far, music education has been unable to attain a higher standing in educational priority than its current “last to support/first to go” status. Perhaps this due to its failings to adequately address the first stated need above. Regardless of the reasons, this puts music education as the last kid to be picked on the team that no one wants to play for.

Music education is too reliant on non-musical rationales.

Music education advocacy efforts were strong in the mid-1990s through the mid-2000s. Leaders in the profession at that time recognized that the arguments used to justify music in schools, many of which are the same used today, were just as ineffective then as they are now. The issue was even discussed by Howard Gardner during his keynote address:

There are numbers of people nowadays who have a dream that music in particular, the arts in general, can be ensconced in the curriculum because of benefits they have that are "extra-artistic." So, there's the notion that involvement in music can make you smarter. And, I guess this is the time when Frances Rauscher became famous. I don't know if it was on the first page of the New York Times, but it was very prominent there that music can make the brain hum. And, I know that Frances thinks sophisticatedly about this, and I'm not even sure we have any quarrel. But, certainly, the idea has caught on that if you play music when the baby is in the womb, or if you're Governor Miller, and you send everybody in Georgia a tape of Beethoven when they are born, that somehow that will make them smarter. This idea has become very much a part of our culture. Another idea is if you engage in the arts such as music, it will make you more creative in business, in science, in your love life, whatever. Another idea is that if you study music or an art form, you will learn how to think critically, and you'll be a better critical thinker in English, history, and so on. My problem with this line of argument is that people who live by instrumental arguments risk dying by them, because if you say the reason to teach music is to make people better in math, and it turns out that it doesn't make people better in math, then you have a real problem in continuing to teach music. Or if you say, well, that music will make you five times better in math, and it turns out that joining the army will make you seven times better in math (I think they're equally improbable), then people will say, "Join the army instead, don't play music." And so, I think it's extremely important for those of us who do favor arts education not to pitch our disciplinary fate to an uncertain guarantor, because if that guarantor fails us, then essentially, we will have marginalized the reasons for any kind of art education, including music education.

Lately, it seems that music education has gravitated back to relying on extra or non-musical justifications for its inclusion in school curricula. Even the letters from NYSSMA and NAfME focused on arguments such as music’s enhancement of academic performance across other subjects and skills such as teamwork, social skills, critical thinking, confidence, etc. Yet, there is little to no mention of the unique things that come with music and the arts that are unique from other school and societal experiences. As Gardner suggested, this puts the strength of the argument at great risk when someone outside the music education bubble only hears the extra or non-musical arguments and rejects them in favor of providing student experiences that are equal to or better than, and, in many cases, cheaper at providing those same opportunities.

Music education is too accepting of mediocrity.

I was fortunate to be a music education student in the mid-1990s to mid-2000s. This was before colleges and universities began drastically cutting degree hours and learning experiences. Since then, I have early 25 years experience teaching in undergraduate and graduate music education programs. I have watched in dismay as degree requirements and important educational experiences have drastically decreased over those years, especially for undergraduate degree programs. All while competing time and financial demands on students have risen to the point of unsustainability. As such, many music educator graduates in the last decade and a half began their careers woefully underprepared to be immediately successful in the classroom. As one former colleague and music education department chair of a large midwestern state university put it to me one time, “Our goal isn’t to make sure our graduates have mastered readiness skills to be teachers but to give them resources they can go to in order to learn what to do to once AFTER they start their careers.” (paraphrase)

Music education has a major discrepancy between stated values and actual practice.

Music education likes to think and claim that it believes in “Music for All” and will fight anyone who says otherwise. However, as pointed out earlier, very few American students are actively participating in music classes. Conventional wisdom says that a healthy number of student participants in school music programs should be 1% of the student population. Schools considered to have a highly successful percentage starts at 10%. That’s a pathetically low bar.

Certainly, this problem is related to both the minuscule number of music experiences offered to American students as well as the low priority status for scheduling, staffing, and financing programs. However, the discrepancy between stated values and actual practice also infects those inside the music education bubble. Activities commonly associated with modern music education are extraordinarily prohibitive for many students who can’t afford the time, money, or servitude needed to keep up with expectations (ahem, ahem…I’m looking at you, marching bands).

So, what can be done not only to better defend against the diminished importance of music education, but to go on the offense and begin gaining allies outside the advocacy bubble? Can we dare to dream of a day when music finds security, priority, and appreciation in American schools and society? Here are some suggestions to start moving the needle towards these aspirations:

WHAT CAN MUSIC EDUCATION DO TO GET OFF THE STRUGGLE BUS?

Music education must figure out how to meet the needs of all citizens, not just those within its bubble.

Look, I understand that this is not a quick or easy fix, and that funding and resources are going to be a problem as long as the American zeitgeist remains apathetic and/or antagonistic towards education. That being said, there are opportunities for music education (as well as all the other humanities) to do a much better job at meeting the humanistic needs that only it can uniquely do. One way to accomplish this is to create curricular models that embrace a more balanced approach to teaching across all three learning domains. For example, the Comprehensive Musicianship Through Performance (CMP) model initiated in Wisconsin in 1977 is a tested approach to include more cognitive domain learning.4

As far as increasing the amount of affective domain activities in the music class, Music Education must first avoid the mistake of believing that this just automatically happens because…duh…music. This isn’t accurate unless the teacher intentionally provides both the safety and the opportunity for students to explore this part of their humanity.

One great way to teach music via the affective domain is to introduce more opportunities for creativity and student contribution to the curriculum. I highly recommend projects such as Jodie Blackshaw’s Teaching Performance Through Composition curricula and works.

I do want to provide some caution regarding one of the current trends in music education. There is much to appreciate about the recent focus on Social-Emotional Learning (SEL) awareness in the music classroom. This is an important part of the aesthetic experience of music learning and in education in general. However, music education must be careful to avoid making SEL its primary purpose, just as it should for any other extra or non-musical justifications. Educators who teach across all three domains and provide frequent opportunities for student engagement will find SEL initiatives a natural outcome of such comprehensive music learning experiences.

Music education must also be more committed to providing every American student an opportunity to express and experience music. Practically speaking, this requires sincere and actionable advocacy for new class offerings and experiences beyond its current curricula. This advocacy needs to begin with fervor within the music education bubble in such a way that it bursts into the broader education world and society at large. Which leads to the next suggestion:

Music education needs to convince the world of its uniqueness and why that matters.

This is probably the most important first step to bring music education out of its defensive posture into a place of value by mainstream society. Gardner provided some great points regarding the uniqueness of music education. I am confident that the current members of the music education bubble can certainly add more. Ultimately, the automatic “go to” of using extra and non-musical justifications needs to cease. I understand why this happens – it’s the only thing people outside the Music Education bubble understands. But it isn’t working, and, like Gardner pointed out, it might actually be hurting. The message needs to be simple – music is worthy and necessary for its own sake. This means music education must collectively embrace what those qualities are and stop putting other priorities, as honorable as they might be, above the purely musical ones. Furthermore, music education must become bold and creative about finding ways to bring those outside the bubble into it’s warm aesthetic biodome.

Music education should advocate and insist on stronger degree and licensure programs and expectations.

This is another area where music education has become too comfortable in its reactionary, victim mentality, partially because of its ineffectiveness in creating and convincing value for anyone outside its bubble. The profession needs visionary and selfless leaders and stronger partnerships between practicing teachers, college and university leadership, and government officials to ensure healthy prioritization of teacher preparation. This is a much bigger issue than just music teacher preparation programs. However, music education has historically been the vanguard for educational reform so why not work to maintain that trend? The future of music in schools is very much at stake. The leaders in higher education must treat it as the existential crisis it is.

Music Education must make the necessary changes in its practices and priorities to bring its values and actions into alignment.

Sadly, this is where I have the least hope in seeing meaningful change. The reality is that so much foundation, identity, ego, etc. is fully enmeshed in the status quo. So much so that it probably needs to fully collapse and be rebuilt from the ground up. I hope I’m wrong and that there are leaders and visionaries with the stamina, intelligence, wisdom, and charisma to excite and encourage wholesale change. Perhaps the best way to start is to have an industry-wide commitment to examine its practices and motives with humility and integrity. This would provide an opportunity to at least identify the areas where word, thought, and deed are not currently in alignment. After all, we are what we DO, not what we SAY or THINK.

FINAL THOUGHTS

This article mainly addresses issues related to music and arts education, but there is a bigger, more consequential concern at play here. Our nation, our humanity needs strong humanities experiences, not just in education, but in life. Looking at things from the 30,000 foot view, it’s easy to see the negative impact that results from huge gaps in affective and cognitive development. It has created an American citizenry where at least half of us lack the virtues of empathy, creativity, kindness, acceptance, critical thinking, and even just joy. Experiences in the arts and humanities, especially during formative years are crucial, not optional, in helping develop these traits. Yes, arts & humanities programs are at risk in the schools. Without them, we will never be able to fix the brokenness and lack of humanity that currently plagues our country.

see “debate regarding military bands” and “Jim Rome marching band” for two relatively recent controversies

Gardner, Howard. “Keynote Address”. Bulletin of the Council for Research in Music Education , Fall, 1999, No. 142, “Cognitive Processes of Children Engaged in Musical Activity” (Fall, 1999), pp. 9-21

An excellent source for a deeper dive into the causes and effects of American Music Education’s infatuation with service, competition, evaluation, and entertainment over the more aesthetic purposes of music is composer/educator/philosopher Jodie Blackshaw’s 2020 doctoral thesis entitled Wearing tone coloured glasses:a ‘colour-first’ compositional approach to the modern wind band as well as the research presented by Jennifer C. Lena and Richard A. Peterson in their article “Classification as Culture: Types and Trajectories of Music Genres” in Volume 73, Issue 5 of the American Sociological Review.

It floors me that Music Education has had this model available for almost half a century but is still largely unknown and unused!